Operations

18 April 2023

Want to reduce returns? A dollar isn’t going cut it

Amazon's $1 return fee at UPS stores poses more risk to the company's brand than return rates.

(Photo courtesy of Amazon)

Amazon's $1 return fee at UPS stores poses more risk to the company's brand than return rates.

(Photo courtesy of Amazon)

You just bought a shirt online, but decided you didn’t want it because it wasn’t the right color. So you opt to send it back.

Returning an item requires putting it back into the same logistics network that just delivered the package, so the service that sent it to you is charging a small fee – one that is a fraction of most shipping charges across the industry. Plus, the fee only applies if certain other locations in the service’s network are closer, and those locations still offer free returns.

That sounds like a pretty good deal, right?

If you’ve just landed on Earth from Mars, maybe. But not in this world, where ecommerce was built by Amazon.

The ecommerce platform made a change to its returns policy that creates just such a system last week, and it is being treated as a bellwether moment for the industry.

As first reported by The Information, Amazon started charging a $1 fee to some customers who make returns through a UPS store. The fee only applies if a Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh or Kohl’s is closer to a customer’s delivery address than UPS.

The policy-level move that applied to a single returns location seemed like the kind of limited test that Amazon often runs en route to figuring out what works, but this was greeted with the fanfare that announces a turning point. Axios wrote that it “calls into question the era of free online returns.” Inc.’s Jason Atem called it a “surprising change” that breaks Amazon’s “most important rule.” “Retail's 'laissez faire' era fades,” blared Yahoo! Finance.

As Nina Simone once said, “This is the world you have made yourself, now you have to live in it.”

Let's take a quick look at how we got here:

As the market leader and pioneering force in ecommerce, Amazon tends to set the standards for the entire space. With a relentless focus on the customer – that rule Atem referenced – the company was at the vanguard of online retailers offering free returns to customers in order to make shopping over the internet as easy as possible. After years of shopping online with these policies in place, customers now expect the flexible return policies of Amazon to be the norm across the web.

But in the process of building that customer-first experience, Amazon also helped to create a mountain of a problem behind the scenes: Free and easy returns are overwhelming logistics networks. This came into the greatest relief when online shopping was at its height during the pandemic. In 2021, one in five items sold by retailers were sent back, according to the National Retail Federation.

Customers liked flexible return policies so much that they stretched the boundaries of home try-on to their limits. Some bought items in a panoply of cuts and colors, only to keep one. It even led to a content opportunity, as Try-On Hauls went viral on TikTok. Returns became just another part of shopping.

But for Amazon, this only created headaches. For one, the company had to figure out what to do with the returned merchandise (Burn it, in some cases, it turned out). Plus, the costs associated with shipping an item back through the supply chain were substantial.

By 2022, the pandemic ecommerce boom was over. The return rate fell somewhat to 16.5% in 2022, according to NRF, but that was still well above 2019 levels and cost retailers $816 billion in sales. Meanwhile, Amazon was seeking to cut costs in its logistics network as it faced down higher fuel prices and the reality that it had overbuilt fulfillment centers for an ecommerce growth trajectory that didn’t last beyond reopening.

Into this walks the $1 return fee. It may appear that the need to rein in costs is finally crashing into founder Jeff Bezos’ longtime refrain to put the customer first. After all, it is hitting on the very real issue of the returns pileup.

What seems more likely is that this fee is designed as test to determine how customers will respond to a change in the return policy, and hone Amazon’s logistics network in the process.

Consider what the policy says, and it appears to be fairly limited in its ability to bring change on its own.

For one, it’s worth noting that the fee is small. Amazon has built a business on tiny changes made at scale that bring outsize returns without anyone noticing. But will customers really blink at a $1 fee? It’s not that much to pay. And even if they do balk, they’re not likely going to jump ship from Amazon. While they may be frustrated by the fee, behind it they will find that they still receive free shipping and fast delivery through Prime. Amazon wired online shoppers’ brains to want what it offers, and it’s unlikely that one fee will short-circuit them.

Closer to the heart of the issue, this policy doesn’t actually seem designed to reduce returns. It’s still very easy to return an Amazon item. After going to a UPS store, a customer may find that they don’t want to pay the fee. But even if they end up keeping that item, they will discover they can go to another location and drop off the next item, and even do so without having to box it up. That's still easy and convenient.

If there is any change, which is not yet determined, the result will only be to push customers to Amazon’s existing network. It owns Whole Foods and Fresh stores, and has a partnership with Kohl’s. As Roger Dooley writes in Forbes, this appears to be a bit of friction engineering.

In fact, the fee seems most likely to be a jab at UPS. The carrier has long considered Amazon’s free returns an existential threat and Amazon has long sought to disentangle from it as it built out its own logistics network.

A more apt test of behavioral change is the introduction of a new badge that labels items as “Frequently Returned.” Also first flagged by The Information, the move to place a label within the shopping experience seems more likely to at least prompt shoppers to think twice about buying an item, if not deterring a purchase altogether. That catches a shopper before they’ve already decided they want to return an item.

Still, it’s clear from the headlines surrounding this fee that there is risk to the perception of Amazon as it introduces new policies during this era of belt-tightening.

If a small change isn’t well received, that could have a big impact. As Atem notes, “Amazon built its brand as the easiest place to order things online, and that includes being the easiest place to return things.”

Amazon’s public relations department seems well aware of this, as they trotted out a blog post last week in the wake of The Information report offering the reminder that “Yes, you can still get free returns on Amazon.”

Even as it seeks to rein in costs, Amazon must carefully consider its relationship with customers with each new update. Thanks to years of focus on ease and flexibility that Amazon made the standard, return policies are now very important to consumers. Data released by Loop last August found that 96% of US consumers believe that a retailer’s return policies directly reflect how much the brand cares about its shoppers, while 54% of consumers said they won’t make a purchase from an online retailer that doesn’t offer free returns. It shows that the language around returns is just as important as behavior. Returns are part of what influences a sale, not just what happens in the post-purchase.

There's also the market to think about. If the Amazon brand is tarnished, it could provide ammunition for others to deliver messaging broadsides against the company with their own and potentially more flexible policies. That could be especially challenging at this time. Amazon is seeking to continue to grow Prime membership. It wants to attract more third-party sellers who are being courted by marketplaces from retailers using Amazon's playbook like Walmart. It is also seeking to build out the Buy With Prime service that expands Prime delivery and – yes – returns to websites beyond the Amazon marketplace. In each of these cases, brand matters. As headwinds stiffen, competition in ecommerce is getting more fierce. Amazon has a big lead, but execution is important.

In that sense, Amazon has a lot to learn from the fee test. A dollar may not actually make Amazon returns harder, but it could say a lot about whether people believe Amazon returns are harder to make. At a retailer where the customer experience is the brand, that’s important. A small change can have a big impact on customer perceptions and expectations, even if it's ultimately the best move for the bottom line.

That's the world Amazon has made for itself, and all of ecommerce. Now it has to live in it.

Amazon partnered with Hexa to provide access to a platform that creates lifelike digital images.

A 3D rendering of a toaster from Hexa and Amazon. (Courtesy photo)

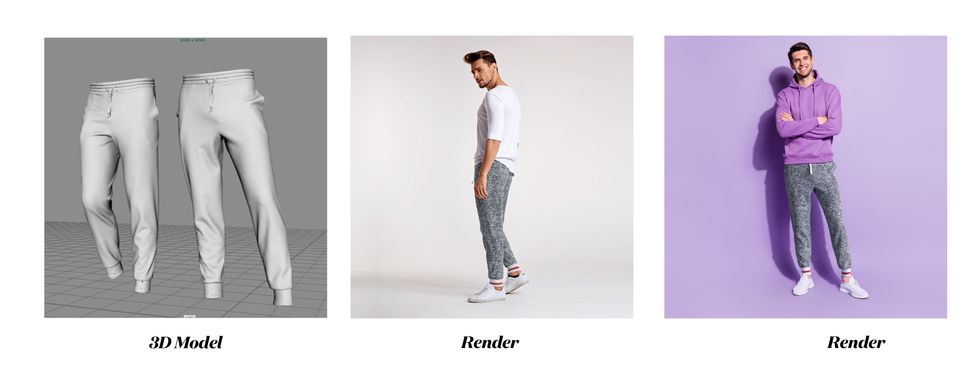

Amazon sellers will be able to offer a variety of 3D visualizations on product pages through a new set of immersive tools that are debuting on Tuesday.

Through an expanded partnership with Hexa, Amazon is providing access to a workflow that allows sellers to create 3D assets and display the following:

Selllers don't need prior experience with 3D or virtual reality to use the system, according to Hexa. Amazon selling partners can upload their Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN) into Hexa’s content management system. Then, the system will automatically convert an image into a 3D model with AR compatibility. Amazon can then animate the images with 360-degree viewing and augmented reality, which renders digital imagery over a physical space.

Hexa’s platform uses AI to create digital twins of physical objects, including consumer goods. Over the last 24 months, Hexa worked alongside the spatial computing team at Amazon Web Services (AWS) and the imaging team at Amazon.com to build the infrastructure that provides 3D assets for the thousands of sellers that work with Amazon.

“Working with Amazon has opened up a whole new distribution channel for our partners,” said Gavin Goodvach, Hexa’s Vice President of Partnerships.

Hexa’s platform is designed to create lifelike renderings that can explored in 3D, or overlaid into photos of the physical world. It allows assets from any category to be created, ranging from furniture to jewelry to apparel.

The result is a system that allows sellers to provide a new level of personalization, said Hexa CEO Yehiel Atias. Consumers will have new opportunity see a product in a space, or what it looks like on their person.

Additionally, merchants can leverage these tools to optimize the entire funnel of a purchase. Advanced imagery allows more people to view and engage with a product during the initial shopping experience. Following the purchase, consumers who have gotten a better look at a product from all angles will be more likely to have confidence that the product matches their needs. In turn, this can reduce return rates.

While Amazon has previously introduced virtual try-on and augmented reality tools, this partnership aims to expand these capabilities beyond the name brands that often have 1P relationships with Amazon. Third-party sellers are an increasingly formidable segment of Amazon’s business, as they account for 60% of sales on the marketplace. Now, these sellers are being equipped with tools that enhance the shopping experience for everyone.

A video displaying the new capabilities is below. Amazon sellers can learn more about the platform here.

Hexa & Amazon - 3D Production Powerhousewww.youtube.com