Operations

25 April 2022

Selecting the right 3PL for gross margin gains

Bainbridge Growth CEO Ben Tregoe provides a cost analysis for DTC businesses.

The right 3PL can deliver gains for DTC businesses.

(Photo by Jake Nebov on Unsplash)

Bainbridge Growth CEO Ben Tregoe provides a cost analysis for DTC businesses.

The right 3PL can deliver gains for DTC businesses.

This post originally appeared on the blog of Bainbridge Growth. It is being republished by The Current with permission.

It is hard to miss the sea of warehouses springing up seemingly overnight in cities all over the US. These facilities are providing the support for ecommerce to grow its proportion of total retail sales to 13% over the last couple of years. The convenience of two-day shipping, wide selection, and product availability are all based on the nearness of the facilities to metropolitan areas. Selecting a fulfillment partner (3PL) with the value add services, scalability, and pricing structure is imperative to your direct-to-consumer business.

Ecommerce as a percentage of retail sales (Image by Bainbridge Growth)

Fulfillment is a broad term, so let’s define that within inbound and outbound fulfillment. Inbound is the receipt of bulk shipments to the warehouse and the subsequent storing and tracking of this inventory using a warehouse management system. Outbound services monitor your order management system for a daily batch of orders and then packs (“packout”) these orders for shipping via your shipping provider that arrives; usually daily, to dock and pick up these orders for processing. An independent non-Amazon DTC business will typically pay a 3PL fulfillment operation explicitly for the square footage in the warehouse(s), per pick variable fees, and management fees.

Let’s look into how to compare these operations based on their pricing structure. Once a DTC operation surpasses a monthly order run rate that requires a certain level of spending on fulfillment services, it will at that point make sense to seek out a third party. Monitoring this intersection of forecasted order counts, AOV and costs should help keep you within a comfortable range of fulfillment costs to revenue on an aggregate and per order basis. Let’s run a quick sketch of that:

*COGs is a flat 50% of AOV (Chart by Bainbridge Growth)

When it comes to driving margin leverage against shipping and fulfillment, the key understanding is the split of fixed versus variable costs. When shipping small parcels, there is a certain cost sensitivity to weight that should allow a business to forecast shipping costs per order within a range. The costs of the 3PL partner for fulfillment-specific services will consist of fixed costs for space charges and management fees. Both of these are related to the amount of space your solution requires, let's say 10K square feet. Variable costs come in when measuring inbound deliveries and cost per pick of SKUs & items per order.

Management fees are typically paid monthly, and serve as a general cost for the 3PL’s basic services, sales support, and warehouse management system reporting. This monthly amount will vary based on the core services selected. Space charges are the other (semi) fixed cost that is based on your forecasted monthly order rate. A fulfillment partner will scope out the amount of space they think is a good fit for your solution and charge you based on a per square foot rate. It is very important to get a good feel for what the right amount of space for your business is because if you forecast orders accurately it will minimize storage costs and help avoid signing on for too much space.

Variable costs are what most are already familiar with, as a warehouse associate moves down an aisle picking 20+ orders at a time, each item pick action is priced and charged to the customer. Assuming a cost of fifteen cents per pick, with duplicates of an SKU done for ten cents the initial rate that cost would look like the following:

(Charts by Bainbridge Growth)

Add the variable cost of 75 cents to $13.00 in fixed costs at 5K monthly orders to reach the all-in total of $13.75. If this number looks relatively high in comparison to AOV, then the business is probably not in need of the full 10K sq feet.

With this price structure, there is clearly moderate leverage gain in getting customers to order in bulk, especially if you sell mostly lightweight items. Large parcels have significantly more dispersion of pick (and shipping) costs, so expect higher per-item costs if your item is large or heavy. On fixed costs there are significant advantages to pushing more orders through the allotted 10k square feet, work with your 3PL to optimize it for the right use of flow and storage.

Value added services are the other primary variable cost, this consists of how many labor hours you purchase for things like high touch pack service, labeling adjustments, or changing the configuration of items in the package. You’d likely end up paying a flat rate of say $40 an hour for these types of services that are performed just before or during the packout process.

Once we understand how to think about a single location, you can apply the same to multiple FCs with some potential for combined management fees across your multi-facility solution. Most companies have facilities strategically located across the US, offering both B2B and B2C capabilities. Be aware that many 3PLs will outline typical ramp up times of roughly 3 - 6 months and charge service start up and integration costs.

As you work through your pricing quote and select a partner, it is best to know your customer and their needs. Make a smart strategic decision on your location, so the product is in close enough proximity to where most of your customers are. Start your process with an accurate orders outlook so that you will scope the right sized solution and carry less risk of price changes based on weaker/strong order flow. The goal should be to efficiently drive volume through your optimized space layout while carrying a rational amount in storage.

Constructor's Eli Finkelshteyn shares principles for responsible use of generative AI, and an experiment.

This is an article about how to approach the use of ChatGPT for improved ecommerce experiences without breaking shopper trust in the process. You probably aren’t expecting Jurassic Park references, but I’m going to make one anyway.

There’s a line of foreshadowing early on where Jeff Goldblum’s character speaks about the complexities and ethics involved in cloning dinosaurs. He says something to the effect of, “Everyone got so excited that they could that they never even stopped to consider if they should.”

ChatGPT, and transformers in general (the technology underlying ChatGPT and a lot of the newer software that’s emerging in the search and discovery world) are incredibly exciting. One of the most exciting parts is how easy it is to build something with ChatGPT, and we’re currently seeing a glut of new software that does just that. Still, what isn’t clear is how to leverage this technology in ways that aren’t just gimmicks, but are actually helpful to people.

It’s clear to just about everyone that we’re in a hype cycle, and that’s why it’s so important for new technology being marketed as “powered by ChatGPT” or “powered by transformers” to prove its business value and usefulness to end users. Not to mix blockbuster movie references, but with great computing power comes great responsibility.

So it’s a good time to ask the multibillion-dollar question: how can technology companies use ChatGPT responsibly and in ways that actually benefit people in the months and years to come?

We’ve adopted some overarching principles internally at Constructor that will serve as our north star as we continue to innovate in this space. As we came up with them, we realized they could be useful as best practices for technology companies in general, and especially those like us who are serving large e-commerce companies. As more and more ecommerce leaders across B2B and B2C evaluate AI solutions in the middle of a hype cycle, we think it’s especially important to publish our principles publicly.

Our hope is that if we stick to these principles, then we’ll maintain our customers’ trust while innovating on new technology, and we’ll do this while doing the right thing for shoppers as well.

Lots of companies can release a cool-looking new product and make claims about its efficacy, but it’s important for all of us to recognize that we’re early in our understanding of what applications of ChatGPT are genuinely useful to humans, and which are just science projects.

Why? Because the vast majority of those results are still unproven.

With ecommerce technology, for example, it’s important to consider whether a technology partner is going to actually deliver a product that has a legitimate impact on revenue or user happiness. Succeeding at that is ultimately a manifestation of extensive experimentation, including testing, failure, iteration, and re-testing — over and over again. Like most good things, data science takes time. It’s complex, and it’s nuanced.

Why is this so important for all of us in ecommerce tech to recognize? Because if we release a bunch of gimmicky technology and promise it’s the next big thing, then when we do come up with something useful, no one is going to trust us anymore.

The critical takeaway here is that any breathless proselytizing about most ChatGPT-based tech at this stage is counterproductive and simply not honest. If a vendor says they know for certain where the gold is right now, it’s just very unlikely to be true.

That’s the critical difference between a culture of experimentation versus one that’s only interested in shipping the “new hotness,” no matter the results. Before a product goes to market, the company that created it needs to be able to explain, and ideally prove, how it will bring ROI.

Is it just a novelty, or will it — in our case as an ecommerce product discovery company — actually help shoppers discover more products they want to buy in a way that’s more convenient, more natural, or more delightful than what they already have? And how do we know?

At Constructor, we’re excited to be experimenting with ChatGPT and large language models and transformers, both internally and with willing customers. We’re excited about the experiments we’re doing, and we hope the customers testing them are too, but we also want to be very clear that these are still just experiments. I’m providing a sneak peek at one experiment we’re very excited about below, but please read on before watching it:

Because here’s what we’re not doing: we’re not claiming we’ve invented the best thing ever. We’re not promising 10000% ROI. This is an experiment we’re excited about, but there is a real possibility that it doesn’t work out.Taking risks is what innovation looks like. The difference is that at the end of the day, our charter is to create real value (and ideally revenue) for our customers — and we won’t sell them a product that delivers anything less.

Ecommerce is full of unique problems and use cases for the ways people find products and content. For example, an add-to-cart and a purchase are both “conversions,” but they’re very much not the same type of conversion. Software that’s built for ecommerce has to understand the distinction, because it’s incredibly important to the KPIs that B2C and B2B ecommerce companies care about.

That’s the primary reason that we built Constructor’s AI core from scratch — the keyword-matching and vector search algorithms that work for general document search just aren’t the best technology to apply to ecommerce product discovery where you have rich feedback from users via their clickstream, along with zero party data like answers in a product-finding quiz. And the same principles apply when we apply ChatGPT to ecommerce.

The idea here is, let’s not try to boil the ocean. We don’t need to create Artificial General Intelligence that can answer every type of human query. We just need to create a very specific form of Artificial Intelligence that does one thing (helping shoppers discover products they’ll love, in our case) very, very well.

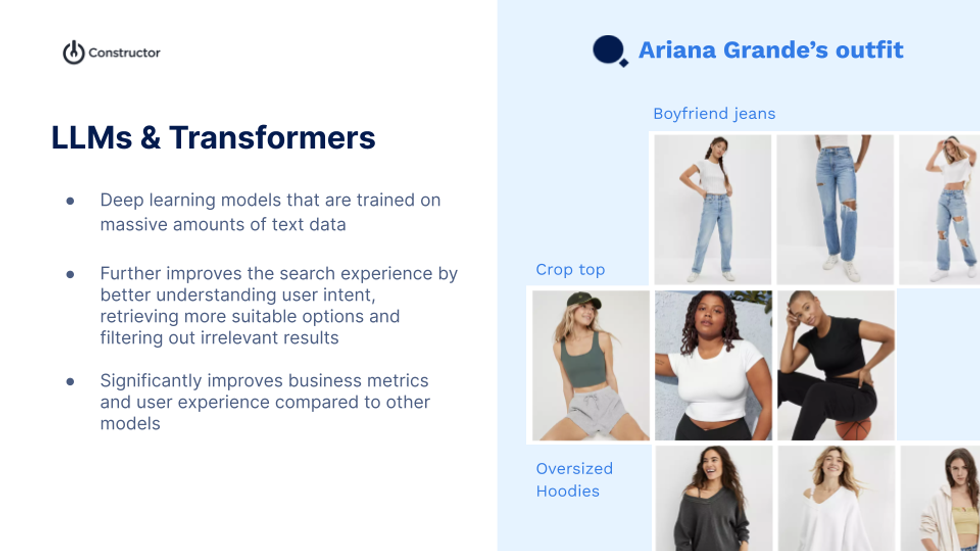

In order to return the most personalized, attractive results to a shopper’s query, ChatGPT needs to be augmented with AI models trained on ecommerce-specific data like clickstream behavior, average order values, margins, and product attributes. What’s really exciting here is that it’s the underlying technology itself that has the potential to completely reshape ecommerce. At Constructor, for example, we are working on using transformers to provide better product retrieval and filter out irrelevant results in search queries. It’s possible that this work may have the greatest impact on customer revenue, even more than the “conversational commerce” element of ChatGPT. But we don’t know yet — that’s why we’re experimenting.

(Image courtesy of Constructor)

Another advantage to training transformers on ecommerce data is that it also might mitigate some of the public concerns around ChatGPT’s accuracy. We only surface products for shoppers based on their own zero-party data and an ecommerce company’s own catalog. This heavily limits the types of wrong answers the system can give, and is about as accurate (and effective) as you can get. You may not be able to ask the ChatGPT solution at your favorite retailer about the year Albert Einstein was born, but it will be much better equipped to help you find a shirt you’ll love, or that one snack you tried and enjoyed, but can’t remember the name of. That’s a sacrifice I think most companies will be willing to make.

We’ll be releasing the full results in the next few months, but our team at Constructor recently performed a survey of 400+ U.S. online shoppers. We found that more than half of them were at least somewhat hesitant about using ChatGPT to find products on websites.

In our current landscape of third-party cookies and data breaches, that response is understandable. And ChatGPT could trigger a similar backlash if it makes shopping uncomfortable or intimidating. New tech can be scary, and it’s a fair concern that you might not want to ask your grocery store to create a shopping list of your regular purchases if it automatically adds sensitive items like gas relief medicine without asking you first.

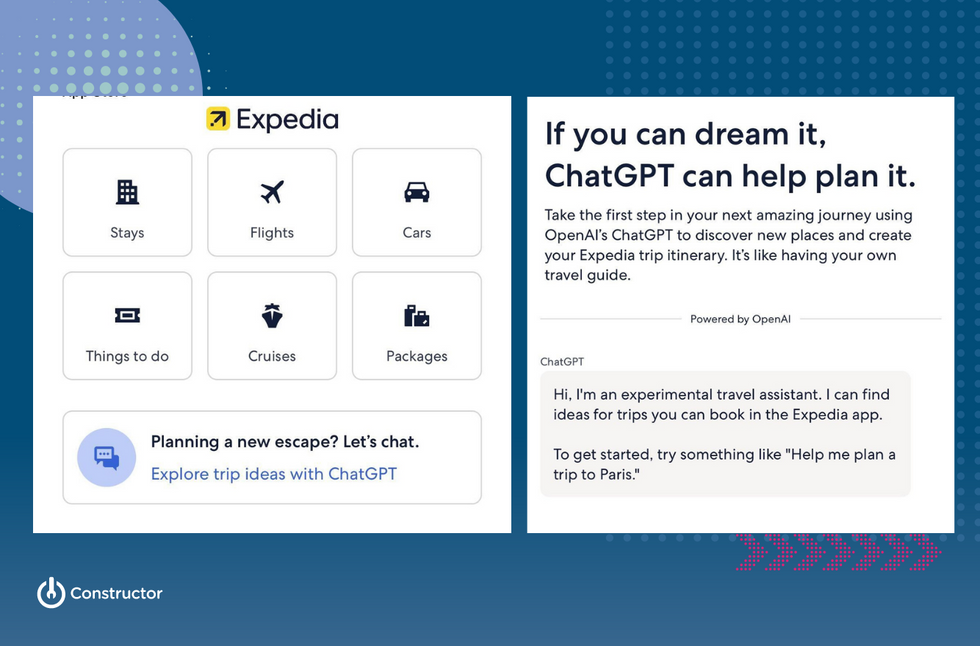

We don’t have all the answers yet (as a company, an industry, or even a society) for how we’re going to solve these problems. Some of it, especially in this experimental phase, will be creating more transparency for the shopper. Expedia is an example of a company approaching this the right way, in my opinion. They recently launched a ChatGPT interface, and they’re very open about it being experimental and not trying to “trick” customers into using it. It’s a small but important step in building customer trust and delivering the value that leads to long-term relationships.

(Image courtesy of Constructor)

Questions will come up as we break new ground here. They’re important to talk and think about, and that work is the shared responsibility of retailers and the partners they work with. Ecommerce companies and their technology partners coming together to consider these murky waters — and being willing to think through new solutions to put customers first — will be absolutely critical.

The amount of excitement and buzz around the (virtual) water cooler here at Constructor when it comes to ChatGPT can’t be overstated. Speed to market is a noble pursuit in this agile, volatile economy, and we are experimenting every day to figure out which of our ideas with ChatGPT and transformers will bring customer value and which require rethinking.

But we also want to balance that excitement with humility. When ChatGPT and transformers are raising legitimate questions from consumers, from companies, and even from others in the AI community, moving forward carefully and intentionally is equally important.

In this retail tech arms race, it’s the companies who widely release technology that doesn’t help their customers that have the most to lose. Ultimately, AI shouldn’t exist just for AI’s sake. Artificial Intelligence needs to yield real value if the companies using it want to be valued by their customers. We hope that our customers have come to trust us for doing right by them and their shoppers, but recognize that trust is something we have to constantly earn and maintain. My hope is these principles will help us and the wider technology ecosystem do exactly that as we embark on this next exciting adventure in AI.

Eli Finkelshteyn is co-founder and CEO of Constructor, an AI-powered product search and discovery platform tailor-made for ecommerce. This piece originally appeared on Constructor's blog, and was reprinted with permission.