Marketing

13 March 2023

The optimization opportunity in retail media

Why last touch attributed sales hide opportunity.

Why last touch attributed sales hide opportunity.

US retail media spend crossed $40B last year, with Amazon taking the lion’s share. eMarketer forecasts that by 2024, this will account for nearly 1 in 5 digital advertising dollars. While the scale of this spend is staggering, what has been truly mind-boggling is the speed at which retail media has reached these levels: search needed a full 14 years to reach $30B in spend, social took 11 years, and retail media has achieved this feat in a mere 5 years.

Retail media has grown under a confluence of factors that make it very difficult to measure effectively. The biggest being that both, the advertising and the sale, take place within walled gardens; and, due to the shifting privacy landscape, there are limited outside options for tracking the customer journey to purchase.

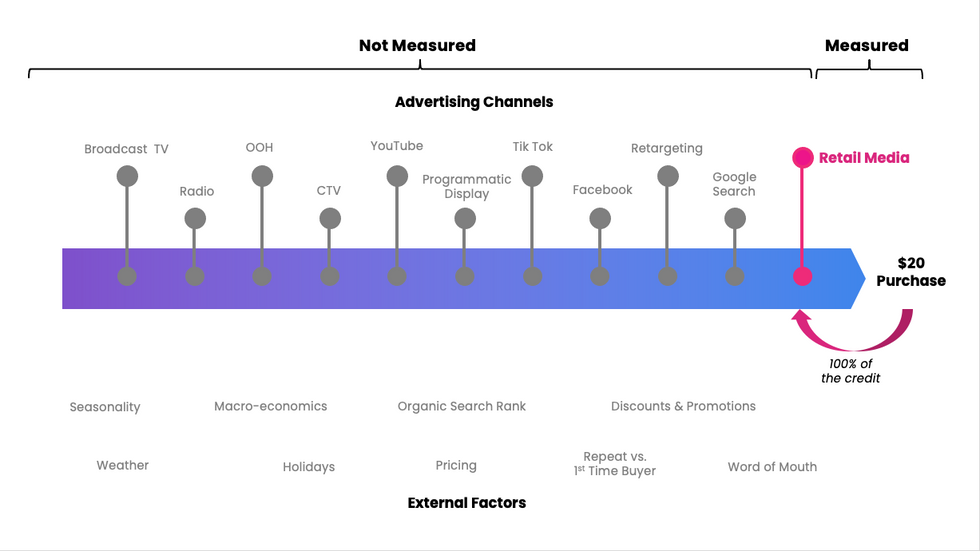

The net result of these conflicting trends toward rapid growth and limited data availability have contributed to widespread adoption of “ad-attributed” sales as the de facto measured outcome of retail media. This metric is widely available and often the default metric across Amazon Ads' own platform as well as the numerous retail media buying platforms. Underpinning “ad-attributed sales” is a very simplistic approach to attribution. If a user saw or clicked an ad and subsequently purchased within the look-back window, the retail media ad gets 100% credit for driving the sale.

When viewed more broadly among all factors which influence a purchase, the rather blunt nature of this approach becomes obvious.

While those users are certainly exposed to an ad, does that ad deserve 100% credit for driving that sale or are there other factors and touchpoints which should be receiving credit as well?

This type of single-source or single-touch attribution has widely been considered inaccurate in almost every other form of advertising and has driven brands and agencies to more nuanced approaches to attribution.

Those of us who have lived through the previous boom cycles of digital media and the catchup game attribution plays will be quick to see the inherent dangers in such an approach to measuring the performance of retail media. Given how close retail media sits to the point of purchase, it can easily take credit for sales being influenced by upstream advertising or external factors like seasonality. There is an analogous set of learnings that came from the early days of digital media. At the time, search and retargeting sat closest to the point of purchase, and because credit was attributed based on the last touch, their performance looked stellar. These channels almost always were the last touch before a user converted. As brands shifted to multi-touch attribution, they came to learn that these channels and tactics were being massively over-credited by last touch attribution.

There was a harder lesson still, learned in the early days of digital which is relevant here as well. Ads on many of these channels were being purchased programmatically using bidding algorithms optimizing toward last touch attributed sales. The result was that the algorithms were optimizing toward users that were the most likely to convert organically so they could touch the users before they converted and steal the conversion credit. The result was huge sums of advertising dollars being directed toward users that actually didn’t need advertising to convert.

Retail media looks to be in a strikingly similar position, with effective measurement lagging behind. The last touch attribution behind “ad-attributed” sales certainly obfuscates what is actually driving sales and just like we saw in the early days of digital advertising, the first wave of platforms providing measurement is usually the same platforms buying or selling the media which introduces questions of misaligned interests and neutrality.

There are a number of alternative approaches to attribution, each with its own tradeoffs. The approach used here draws from multivariate time series models. These types of time series models have a long history in attribution and are the underpinnings of most marketing mix models today. They attribute sales based on a multitude of factors which influence the outcome, including other media channels like search and social, promotions, and even seasonality and holidays. The results below are an aggregate of these models across a broad set of brands and retail media campaigns.

Before we dive into the results, let’s establish a few operational definitions to ensure we are all speaking the same language:

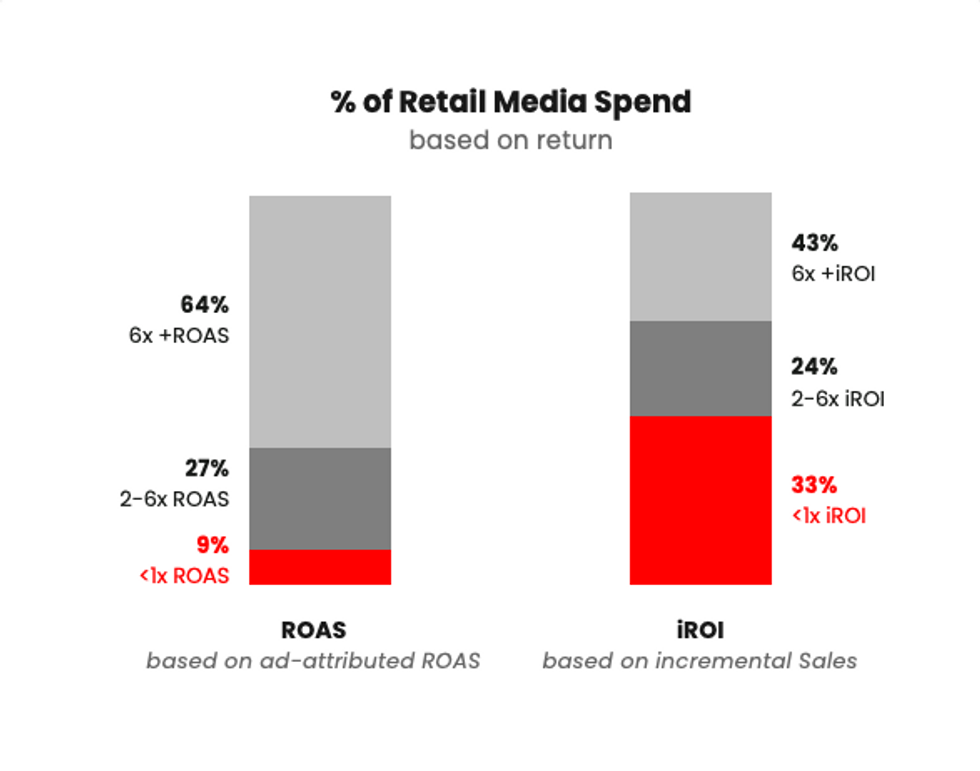

While there are some other interesting insights that have come out of this work (more on those in a later post) I’ll focus on only two here:

Now there is a silver lining to the second point – this is a huge optimization opportunity. Across the industry, that 33% would add up to over $10 billion worth of investment that could be optimized. If those poor-performing campaigns can be identified quickly and that budget reallocated to stronger-performing retail media campaigns, brands can generate significant additional sales with the same working retail media budget.

Now, not all campaigns with iROI of < 1x should be seen as a “bad” investment. Some may serve a strategic value like bidding on branded keywords to protect the brand from competitive conquesting but there is certainly some additional juice that can be squeezed out of retail media with some more robust measurement.

This comes down to last-touch attribution obfuscating the true value of retail media. When looked at under the lens of a more nuanced approach to attribution, there were plenty of retail media campaigns which drove fantastic ROI but last touch attribution blurs those campaigns with ones that are not producing strong returns.

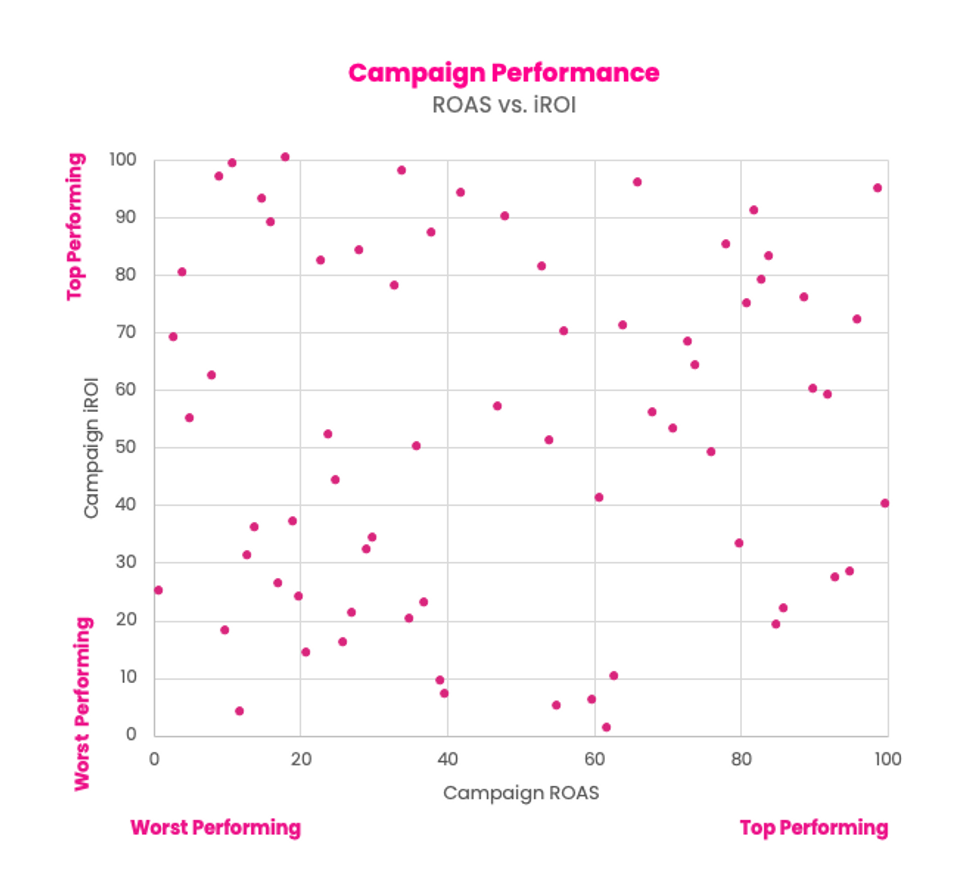

To illustrate this, we compared ROAS and iROI at a campaign-level. One might expect a generally positive relationship between the two. The top performing on one side likely being the top performing on the other.

The results are Jackson Pollock-esque to say the least:

The campaigns that last touch attribution suggested were top performers were not the ones to which our attribution model gave the most credit. Last touch attribution simply is not effective at identifying the actual winners and losers at a campaign level. The upside here is that a more nuanced attribution approach, can become a source of competitive advantage for brands that move first. They should be able to optimize their retail media investments far more effectively than their peers still using last touch attribution.

There is absolutely a maturity curve to climb in measuring retail media and we are still in the early days as an industry. The good news is that there is a wealth of alternative approaches to measuring retail media other than the last touch attribution being used today and there is a lot we can learn from the hard-won yards in other media channels that we can apply here to avoid making the same mistakes twice.

New advertising opportunities are being beta tested for in-store audio and product demos.

Retail media’s fast growth isn’t only limited to increasing spend. The advertising itself is also poised to appear in more places beyond ecommerce marketplaces, and even beyond the web.

The latest example comes from Walmart Connect, which is the retail media arm of the world’s largest retailer.

Walmart shared details on testing that it is completing for in-store retail media. To this point, Walmart Connect has been considered the advertising platform for Walmart’s ecommerce site. But these tests indicate that’s poised to expand.

Stores present a potent opportunity for Walmart. It has 4,700 big box locations around the U.S., and customers returned to them in droves last year. In 2022, 88% of the retailer’s customers visited Walmart stores.

Walmart Connect already has already dipped a toe into in-store advertising, with a TV wall, self-checkout ads and integrated marketing. The new pilots aim to take a step further.

“The next frontier of retail media is in-store experiences, and it’s one we’re excited to chart,” Whitney Cooper, head of omnichannel transformation at Walmart Connect, wrote in a blog post on the new tests. “But it’s still an emerging opportunity for us, as we continue to test what serves customers best and which solutions are scalable to Walmart’s size.”

Here’s a look at the two new offerings currently under beta test:

Walmart suppliers will be able to integrate product demos into campaigns across in-store and digital environments.

Product demos aren’t new to store floors, but Walmart Connect is seeking to give them an update that blends digital and physical experiences.

“Part of our test is how to enhance the omnichannel experience by bridging the physical back to digital: For example, by pairing a demo cart with QR codes that link back to a curated Walmart.com landing page so customers can find inspiration and shop their list all in one spot,” Cooper wrote.

Walmart is currently offering 120 demos at stores each weekend, and plans to scale to 1,000 by the end of 2023.

Walmart Connect will now offer advertising placements on Walmart’s in-store radio network. Suppliers will have the option to purchase ads by region or store, enabling targeting of key markets.

“This is the first time brands will be able to speak directly to Walmart customers through this medium,” Cooper writes. “These ads also create a new upper-funnel touchpoint for brand marketers and out-of-home (OOH) buyers to create awareness, because in-store audio is about connecting with customers wherever they are in the store — they don’t have to pass the brand in the aisle.”

With the tests, we’ll be watching for how this advertising is measured, and whether Walmart Connect is tracking impact across different types of formats, and not just a single campaign.